The Historical Significance of Acheulean Handaxes in Medieval Art

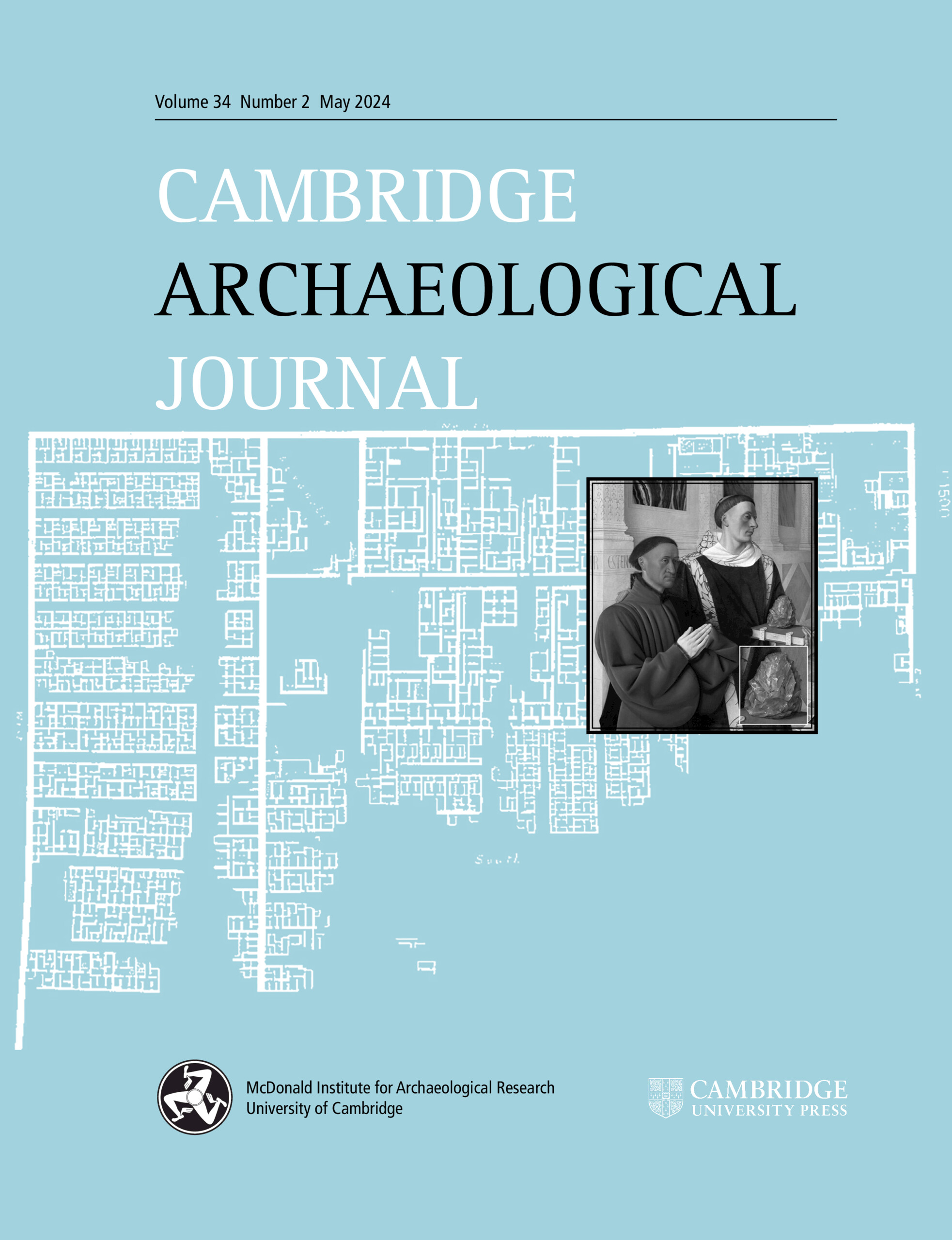

Acheulean handaxes, significant Palaeolithic artefacts, have a complex social history that can be traced back to the mid-1600s in England, coinciding with increased interest in antiquities during the European Enlightenment. However, evidence suggests their recognition and potential usage in society may extend further back, possibly to the fifteenth century. The painting "Étienne Chevalier with Saint Stephen" by Jean Fouquet, created around 1455, features a stone object that closely resembles an Acheulean handaxe. Through shape, color, and flake scar analyses, researchers propose that this depiction could indicate an awareness of these ancient tools in medieval France, thereby pushing back the timeline for their social significance. The handaxe may symbolize a connection to divine or extraordinary natural phenomena, reflecting its potential importance in religious or social contexts of the time.

- Acheulean handaxes have been studied since the mid-1600s, tied to the rise of archaeology.

- The painting by Jean Fouquet possibly represents an Acheulean handaxe, suggesting earlier awareness of such objects.

- Analyses of the painting indicate the stone's shape and color align with known Acheulean features.

- The presence of the stone in a religious context hints at its symbolic significance in medieval society.

What are Acheulean handaxes?

Acheulean handaxes are prehistoric stone tools characteristic of the Palaeolithic era, known for their distinctive bifacial flaking and widespread archaeological presence.

Why is the painting by Jean Fouquet significant?

The painting is significant because it may depict an Acheulean handaxe, suggesting that these prehistoric tools were recognized and held social or religious meaning in medieval France.

How does the research push back the timeline for the social significance of handaxes?

The research indicates that the social history of handaxes may extend to the fifteenth century, much earlier than previously recorded instances of their recognition as human-made objects.